Germany’s New Wine Law: Order, Overlap, and the Confusion That Still Lingers

The 2021 German Wine Law promises clarity. But as it takes full effect with the 2025 vintage, questions remain: who does it really help—and who gets left parsing the fine print?

⚠️ Warning: German wine law ahead.

Expect vineyard names, label logic, and a bit of alphabet soup. But also: why this matters more than you think—for your next bottle of Riesling and for the future of wine storytelling.

When Clarity Creates Complexity

Germany has never lacked precision. But when it comes to wine classification, that precision has often come wrapped in layers of rules, exceptions, and acronyms. Labels whisper of Spätlese, Trocken, or Goldkapsel—and sometimes shout nothing at all about style or quality.

In 2021, the German government introduced a bold revision of its wine law. The goal: bring clarity by shifting focus from ripeness at harvest to geographic origin. With the 2025 vintage, this new law becomes fully effective. But in a classic twist, it doesn’t replace the old system—it layers on top of it.

So what does that mean for you? For the wine trade? For students trying to make sense of the label?

That’s where it gets interesting.

From Ripeness to Region: The Pivot

Historically, German wine law was built on must weight—a measure of sugar in the grapes at harvest. The higher the must weight, the more “distinguished” the wine, with Kabinett through Trockenbeerenauslese forming the Prädikatswein ladder. But this didn’t always align with style, sweetness, or quality.

Enter the VDP, a group of leading producers founded in 1910 to promote naturally made, high-quality wines—long before today’s classification debates. Frustrated with the sugar-based system of the 1971 wine law, the VDP later developed its own model emphasizing vineyard quality and dry wine typicity, mirroring Burgundy’s structure:

Gutswein → Ortswein → Erste Lage → Grosse Lage,

with GG (Grosses Gewächs) representing their top-tier dry wines from the best vineyard parcels.

The 2021 Wine Law aims to bring similar geographic logic into national law. It introduces a new hierarchy:

Anbaugebiet – Wine region (e.g., Mosel, Rheingau)

Region – Replaces old Bereich/Grosslage

Ortwein – Village-level

Einzellage – Single vineyard

But here's where it gets especially important: within Einzellage, the new law now officially defines two premium tiers—and they're not the same as the VDP system.

🔎 Under the legal system, top wines from single vineyards may now be classified as:

Erstes Gewächs (First Growth)

Grosses Gewächs (Great Growth)

These designations come with specific rules on yield, grape variety, hand-harvesting, alcohol level, and release dates—and they must be dry.

This is a big shift. Because now, Grosses Gewächs isn’t just a VDP term with a trademarked logo—it’s also a legal term any qualifying producer can use on the label.

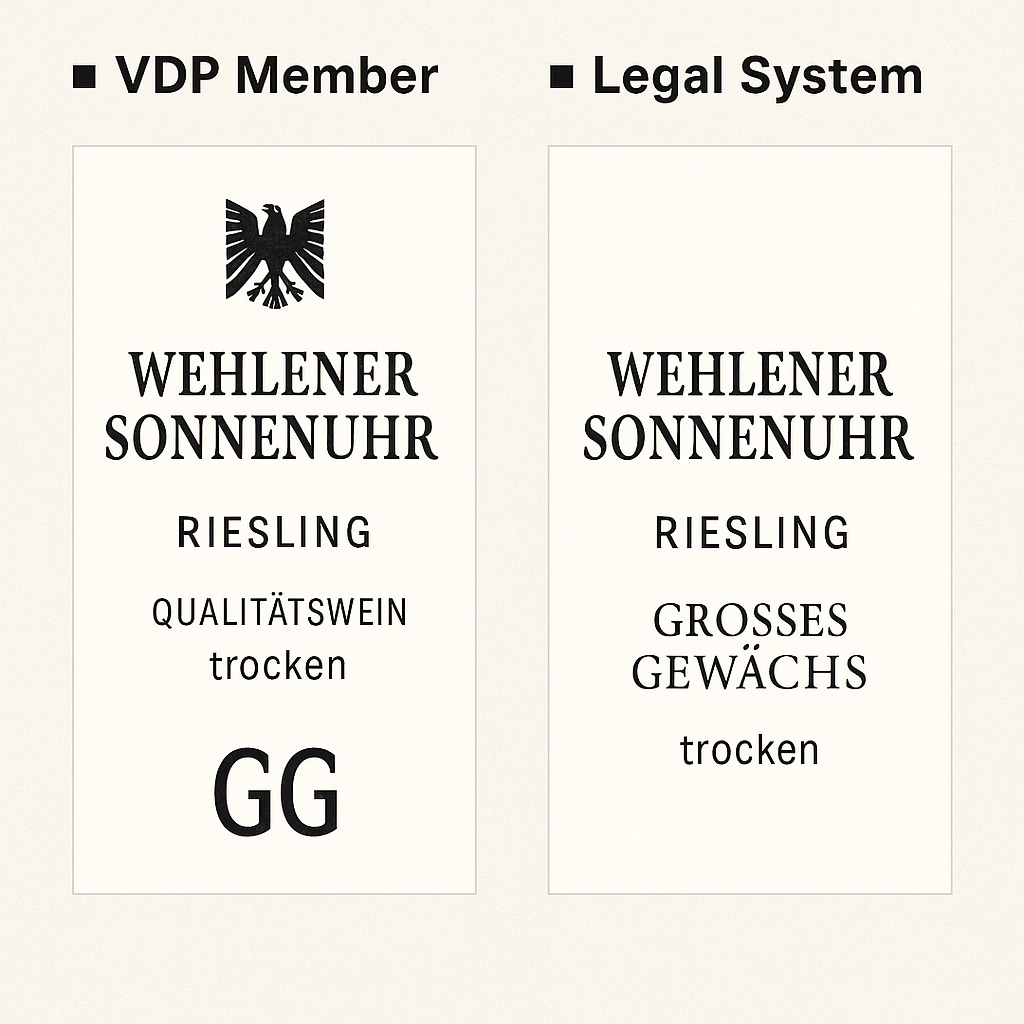

So what happens when one vineyard—say, Wehlener Sonnenuhr—is farmed by two producers? One in the VDP, the other not?

Let’s take a look.

Case Study: Same Vineyard, Same Vintage—Very Different Labels

📌 Wehlener Sonnenuhr, 2025 vintage

Producer A – A VDP member

Labels their top dry Riesling as Qualitätswein trocken with the discreet VDP eagle and GG logo. They’re not allowed to write Grosses Gewächs on the label—but under the VDP, this is understood as the top-tier dry wine from a Grosse Lage vineyard.Producer B – Not in the VDP

Labels their dry Riesling as Grosses Gewächs trocken, following all legal requirements. They can spell it out because they’re using the term under state law, not the private VDP system.

Both wines:

Come from Wehlener Sonnenuhr, a famous Mosel vineyard

Say Riesling

Refer to Grosses Gewächs

But only one follows the VDP’s internal rules. And only one uses the VDP’s trademarked “GG” symbol. From the outside, they look similar. But their meaning—and quality assumptions—can be very different.

Visual comparison:

The Transition Period: Expect Hybrid Labels Through 2026

Even though the law officially takes effect with the 2025 vintage, producers have until the end of 2026 to fully adapt labeling and geographic indications.

This means:

Terms like Grosslage (large collective vineyard names) may still appear until 2026

Prädikat levels (Kabinett, Spätlese, etc.) remain part of the law, but their use on dry wines may continue to cause confusion

New geographic tiers (Region, Ortwein, Einzellage) will roll out unevenly depending on region and producer readiness

Wines labeled “Grosses Gewächs” might follow VDP or legal criteria—with very different implications

For educators, consumers, and D3 students alike, staying fluent in both systems will be essential through at least 2027.

What to Know for Trade and D3

If you work in wine—or study it—here’s what to watch for:

Know the legal and VDP pyramids—and where they overlap or diverge

Understand that “Grosses Gewächs” spelled out on a label refers to the legal classification

“GG” as a symbol is a VDP trademark and only used by VDP members for dry wines from Grosse Lage sites

Look for release dates, yields, and vineyard tiers as clues to style and quality

Don’t assume that a wine labeled Grosses Gewächs is VDP—check for the eagle logo and GG trademark

Conclusion: A Step Forward, With Labels Still Catching Up

The 2021 Wine Law was a move in the right direction. Germany is trying to tell a clearer story—one that celebrates origin, structure, and place. But by keeping the old system alive during the transition, and by not fully aligning with the VDP, it’s also left room for confusion.

The risk is simple: a term like Grosses Gewächs may now mean more and less at the same time, depending on who made the wine.

Germany’s wine identity is evolving. But the new map, for now, still comes with a legend—and a learning curve.